…So be smart with what you’ve got!

I’ve been talking to a number of young women in recent months. When I do this, two thoughts stay uppermost in my mind:

I’ve been talking to a number of young women in recent months. When I do this, two thoughts stay uppermost in my mind:

-Carole, do not expect these fresh faces to listen in an attentive and fascinated way while you blah on about pensions

-Whoa, you’re young.

Two reports and some home truths

I try not to let this second thought depress me as it is the very reason why I am talking to them in the first place. Catching women while they are in the first phase of their adult lives to slap them around the face with some home truths about their finances is not always a welcome move. And I sense that they don’t always believe what I am saying. So I was delighted (in a shallow and flippant way) when two reports were released in March this year that gave me some concrete figures with which to bombard my listeners:

- A report from Scottish Widows on Women in Retirement calculating that a woman in her twenties today will have £100,000 less in her pension at retirement age than a man of the same age

- Data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) showing that women with dependent children are 7 times more likely to work part time than men

(Please see the ‘A bit more understanding’ section at the end for more detail if you love a good stat).

Be smart with what you’ve got

It is numbers like these that help to hammer home the point of my talk for younger women: life’s not fair so you have to smart with what you’ve got. This is a tough message for a 20-something. I’m basically telling them that they need to start preparing for old age when they can barely see beyond the next episode of Bridgerton (I sense that this is a reference that is already woefully out of date – but you get my drift).

Equality: ‘We’ve got this’

So it’s helpful to have reports that attempt to quantify these things, because £100,000 is a lot of money and young women are often shocked by it. Living in an echo chamber with only their peers for company they may have come to believe – as I think my friends and I did back in the 1980s and 90s – that, when it comes to gender equality, they’ve ‘got this’. And so I find myself having to disillusion them a little by explaining exactly how the amount that eventually ends up in an oldie’s pension pot is arrived at.

It’s all connected to gender

In this explanation we dance a bit around topics like risk and growth but there is no getting away from the fact that the most fundamental factor in how much you will get from your pension in retirement is how much you put into it. And then I get a bit knee-bone-connected-to-the-thigh-bone on them as I explain that how much you put in depends on how much you earn, and that how much you earn over your lifetime can depend on a whole bunch of stuff – one of which is your gender.

Be aware of the general state of play

I’m always at pains to point out here that this is not something that is set in stone irrevocably forever more – and that reports such as the Scottish Widows one will be based on a number of assumptions that will be variable. To a large extent it will be up to this generation to take up the fight but, for now, it does no harm for them to be aware of the general state of play. First up, the types of degree and career that young women are choosing still show a gender bias, which, when it comes to earnings power, is not in their favour.

The top line represents the men

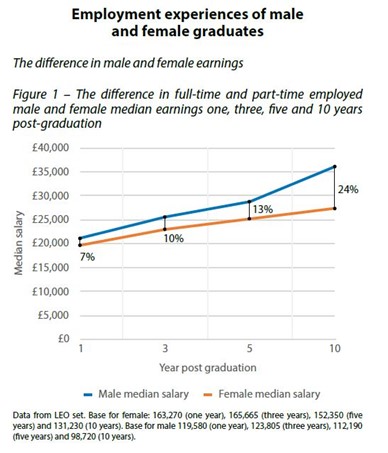

The chart below shows the difference in women’s and men’s pay one, three, five and ten years after graduation. If you can’t be bothered to look at the detail, all you need to know is that the top line represents the men.

The disparity that exists just one year after graduation tells a story in its own right but the other stark reality that jumps out from the chart is what happens five-plus years down the line when these young women and men are into the second half of their twenties. It can’t be a coincidence that this is when so many of them will be embarking on big life changes such as having children.

Choices that depress your earnings

Starting a family almost inevitably has an effect on how much a person earns – whether that’s because of taking a career break, going part-time or downshifting a career to one that fits more easily into family life. Like it or not, it is still largely women who are making these earnings-depressant choices and – as I may have already mentioned – how much you earn affects how much you have in your pension.

It’s down to you

None of this is news. And none of it is a revelation. It stands to reason that if you don’t put as much into your pension as the next man (and that’s not a generic man), you will have less at the end of your working life. What is a revelation to these young women, however, is that it is going to be down to them to manage this situation. When they make a life decision that will affect their earnings, they need also to check the effect that it is going to have on their pension. No one else will think to do that for them and I believe they deserve a heads-up on this. Because, if they don’t do anything about it, there’s a good chance they will end up with that £100,000 pension gap as predicted by Scottish Widows.

Go big and go early with your savings!

The good news for anyone in this age bracket – and whilst that might not be you, dear Reader, it might be your daughters, grand-daughters, nieces or family friends – is that they are young. The message is: you have time on your side to get your money working, so, go big and go early with your savings!

A quick quiz

On this note, there’s a little quiz I like to do:

Who will have the most money at age 60?

- Saver A who puts £100 a month by for 15 years between the ages of 20 and 35 and then leaves it to grow; or

- Saver B who puts £100 a month by for 30 years between ages 30 and 60.

The answer is Saver A who, if we assume both savers get a fantasy growth rate of 5% a year, would be over £8,000 better off than Saver B at age 60, despite Saver B having put twice as much aside.

The young can afford to sit out the wobbles

The example shows the power of compound interest over long periods of time – and this is something that applies equally to savings or investments or indeed anything that grows! Long timeframes in the investing world have also historically had the advantage of lessening the likelihood of losses. This is because, when a sharp downturn happens in the investment markets (such as we saw in 2020), they do need time for recovery. When you are young, time is something you have plenty of – so you can afford to sit out the wobbles.

It’s bad news and good news

So there’s bad news and good news for young women savers. The bad news is you are statistically likely to earn less than a man throughout your working life and therefore have less in your pension. The good news is, if you are aware of this early enough, you can do something about it. For example, that same report from Scottish Widows indicated that paying an additional 5% into your pension at the start of your working life can go a long way towards evening out the gender difference. Everyone’s situation is different and will require different planning – but putting a bit more into a pension early on in your working life is generally a good idea, as long as you can afford to.

Another thought springs to mind

I started this post by sharing the two thoughts that occupy me when I talk to young women about saving for their futures. There’s another one that often springs to mind – I wish someone had told me this when I was young. If you know of any young women entering adulthood who you think would benefit from a 45-minute presentation to give them a heads-up on this, do drop me a line.

3 May 2021

www.talkingfinances.co.uk/blog/

Talking Finances is a trading name of Talking Finances Ltd. Talking Finances Ltd is an appointed representative of Beaufort Financial Planning Limited, Kingsgate, 62 High Street, Redhill, Surrey, RH1 1SH, which is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, FCA Registration No. 583233

This article represents the personal opinion of Carole Haswell only and does not represent any opinion of Beaufort Financial Planning Limited. Financial decisions should not be made on the basis of this article

A bit more understanding

- The male and female graduate pay chart is from a report called ‘Mind the (Graduate Gender Pay) Gap’ published in 2020 by the Higher Education Policy Institute and based on 2017 data from HMRC, the DWP and DfE

- The Scottish Widows Women & Retirement Report was published on 8 March 2021 and can be accessed through their website

- The following ONS data was released on 8 March 2021 under Families and the Labour Market (based on surveys carried out between July and September 2020):

- Women with dependent children are 7x more likely to work part time than men;

- Only 25% of mothers with a one-year-old work full time;

- 15% of mums versus 1.9% of dads say they are economically inactive because of their caring duties.